German Art History and Scientific Thought Beyond Formalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and exam of cognition"[ane] or "whatsoever view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".[ii] More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory simply intellectual and deductive".[3]

In an old controversy, rationalism was opposed to empiricism, where the rationalists believed that reality has an intrinsically logical structure. Because of this, the rationalists argued that certain truths exist and that the intellect can directly grasp these truths. That is to say, rationalists asserted that certain rational principles exist in logic, mathematics, ideals, and metaphysics that are so fundamentally true that denying them causes ane to fall into contradiction. The rationalists had such a high confidence in reason that empirical proof and physical evidence were regarded as unnecessary to define certain truths – in other words, "at that place are significant ways in which our concepts and knowledge are gained independently of sense feel".[4]

Different degrees of accent on this method or theory lead to a range of rationalist standpoints, from the moderate position "that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge" to the more farthermost position that reason is "the unique path to knowledge".[five] Given a pre-modern understanding of reason, rationalism is identical to philosophy, the Socratic life of enquiry, or the zetetic (skeptical) clear estimation of authority (open to the underlying or essential cause of things every bit they announced to our sense of certainty). In recent decades, Leo Strauss sought to revive "Classical Political Rationalism" as a discipline that understands the task of reasoning, not equally foundational, just as maieutic.

In the 17th-century Dutch Republic, the rise of early modern rationalism – equally a highly systematic school of philosophy in its own correct for the first time in history – exerted an immense and profound influence on modern Western thought in general,[6] [vii] with the nascency of two influential rationalistic philosophical systems of Descartes (who spent most of his developed life and wrote all his major work in the United Provinces of kingdom of the netherlands)[8] and Spinoza–namely Cartesianism and Spinozism. 17th-century arch-rationalists such as Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz gave the "Historic period of Reason" its name and place in history.[9]

Background [edit]

Rationalism — as an appeal to human reason as a way of obtaining noesis — has a philosophical history dating from artifact. The analytical nature of much of philosophical enquiry, the awareness of apparently a priori domains of knowledge such as mathematics, combined with the emphasis of obtaining knowledge through the use of rational faculties (commonly rejecting, for example, straight revelation) take fabricated rationalist themes very prevalent in the history of philosophy.

Since the Enlightenment, rationalism is normally associated with the introduction of mathematical methods into philosophy as seen in the works of Descartes, Leibniz, and Spinoza.[3] This is commonly called continental rationalism, considering information technology was predominant in the continental schools of Europe, whereas in Britain empiricism dominated.

Even and then, the distinction betwixt rationalists and empiricists was fatigued at a subsequently period and would not accept been recognized by the philosophers involved. Also, the distinction betwixt the two philosophies is not as clear-cut as is sometimes suggested; for example, Descartes and Locke have similar views well-nigh the nature of human ideas.[iv]

Proponents of some varieties of rationalism fence that, starting with foundational basic principles, like the axioms of geometry, one could deductively derive the remainder of all possible knowledge. Notable philosophers who held this view most conspicuously were Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Leibniz, whose attempts to grapple with the epistemological and metaphysical problems raised by Descartes led to a development of the fundamental approach of rationalism. Both Spinoza and Leibniz asserted that, in principle, all cognition, including scientific knowledge, could exist gained through the use of reason alone, though they both observed that this was non possible in practice for human beings except in specific areas such as mathematics. On the other hand, Leibniz admitted in his book Monadology that "we are all mere Empirics in three fourths of our actions."[5]

Rationalism was criticized by American psychologist William James for beingness out of touch with reality. James too criticized rationalism for representing the universe equally a airtight system, which contrasts to his view that the universe is an open organisation.[10]

In politics, rationalism, since the Enlightenment, historically emphasized a "politics of reason" centered upon rational choice, deontology, utilitarianism, secularism, and irreligion[xi] – the latter aspect's antitheism was subsequently softened past the adoption of pluralistic reasoning methods practicable regardless of religious or irreligious credo.[12] [13] In this regard, the philosopher John Cottingham[14] noted how rationalism, a methodology, became socially conflated with atheism, a worldview:

In the by, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, the term 'rationalist' was often used to refer to complimentary thinkers of an anti-clerical and anti-religious outlook, and for a time the word acquired a distinctly debasing forcefulness (thus in 1670 Sanderson spoke disparagingly of 'a mere rationalist, that is to say in plain English an atheist of the late edition...'). The use of the characterization 'rationalist' to characterize a world outlook which has no place for the supernatural is becoming less pop today; terms like 'humanist' or 'materialist' seem largely to take taken its identify. But the old usage however survives.

Philosophical usage [edit]

Rationalism is frequently assorted with empiricism. Taken very broadly, these views are not mutually exclusive, since a philosopher can be both rationalist and empiricist.[2] Taken to extremes, the empiricist view holds that all ideas come to us a posteriori, that is to say, through feel; either through the external senses or through such inner sensations as pain and gratification. The empiricist substantially believes that knowledge is based on or derived directly from experience. The rationalist believes we come to knowledge a priori – through the use of logic – and is thus contained of sensory experience. In other words, as Galen Strawson once wrote, "you lot can come across that it is true just lying on your couch. You don't have to get upwards off your burrow and get outside and examine the way things are in the physical earth. You don't have to practise any science."[15]

Betwixt both philosophies, the consequence at hand is the primal source of human knowledge and the proper techniques for verifying what we think we know. Whereas both philosophies are under the umbrella of epistemology, their argument lies in the understanding of the warrant, which is under the wider epistemic umbrella of the theory of justification. Part of epistemology, this theory attempts to sympathise the justification of propositions and beliefs. Epistemologists are concerned with various epistemic features of belief, which include the ideas of justification, warrant, rationality, and probability. Of these four terms, the term that has been nearly widely used and discussed by the early on 21st century is "warrant". Loosely speaking, justification is the reason that someone (probably) holds a belief.

If A makes a claim and and then B casts doubt on it, A's next move would normally exist to provide justification for the merits. The precise method ane uses to provide justification is where the lines are drawn between rationalism and empiricism (among other philosophical views). Much of the debate in these fields are focused on analyzing the nature of knowledge and how information technology relates to connected notions such every bit truth, belief, and justification.

At its core, rationalism consists of 3 bones claims. For people to consider themselves rationalists, they must prefer at least one of these iii claims: the intuition/deduction thesis, the innate knowledge thesis, or the innate concept thesis. In addition, a rationalist can cull to prefer the merits of Indispensability of Reason and or the claim of Superiority of Reason, although i can be a rationalist without adopting either thesis.[ commendation needed ]

The indispensability of reason thesis: "The cognition we gain in subject expanse, Southward, by intuition and deduction, also as the ideas and instances of knowledge in Due south that are innate to us, could non have been gained by u.s.a. through sense experience."[1] In brusque, this thesis claims that experience cannot provide what we gain from reason.

The superiority of reason thesis: '"The knowledge we gain in subject area S by intuition and deduction or have innately is superior to whatsoever knowledge gained past sense experience".[ane] In other words, this thesis claims reason is superior to experience every bit a source for knowledge.

Rationalists often adopt similar stances on other aspects of philosophy. Most rationalists reject skepticism for the areas of knowledge they claim are knowable a priori. When yous merits some truths are innately known to us, one must reject skepticism in relation to those truths. Especially for rationalists who adopt the Intuition/Deduction thesis, the idea of epistemic foundationalism tends to ingather up. This is the view that we know some truths without basing our conventionalities in them on any others and that we then use this foundational knowledge to know more truths.[ane]

The intuition/deduction thesis [edit]

"Some propositions in a particular subject area, S, are knowable by us past intuition alone; even so others are knowable by being deduced from intuited propositions." [16]

Generally speaking, intuition is a priori knowledge or experiential belief characterized by its immediacy; a form of rational insight. We simply "meet" something in such a way equally to give us a warranted belief. Beyond that, the nature of intuition is hotly debated. In the same way, more often than not speaking, deduction is the process of reasoning from one or more full general premises to attain a logically sure determination. Using valid arguments, we can deduce from intuited premises.

For instance, when nosotros combine both concepts, we can intuit that the number three is prime and that it is greater than two. We and so deduce from this cognition that there is a prime number greater than two. Thus, information technology can be said that intuition and deduction combined to provide us with a priori knowledge – we gained this knowledge independently of sense experience.

To argue in favor of this thesis, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent German philosopher, says,

The senses, although they are necessary for all our actual knowledge, are not sufficient to give us the whole of it, since the senses never give anything but instances, that is to say particular or individual truths. Now all the instances which confirm a general truth, nonetheless numerous they may exist, are non sufficient to establish the universal necessity of this same truth, for it does not follow that what happened earlier volition happen in the same way again. … From which information technology appears that necessary truths, such as we find in pure mathematics, and particularly in arithmetic and geometry, must have principles whose proof does not depend on instances, nor consequently on the testimony of the senses, although without the senses it would never take occurred to u.s. to retrieve of them…[17]

Empiricists such as David Hume have been willing to accept this thesis for describing the relationships among our own concepts.[sixteen] In this sense, empiricists argue that we are allowed to intuit and deduce truths from knowledge that has been obtained a posteriori.

By injecting different subjects into the Intuition/Deduction thesis, we are able to generate different arguments. Most rationalists agree mathematics is knowable past applying the intuition and deduction. Some go further to include ethical truths into the category of things knowable by intuition and deduction. Furthermore, some rationalists also claim metaphysics is knowable in this thesis. Naturally, the more subjects the rationalists merits to be knowable by the Intuition/Deduction thesis, the more certain they are of their warranted behavior, and the more strictly they adhere to the infallibility of intuition, the more controversial their truths or claims and the more radical their rationalism.[16]

In addition to different subjects, rationalists sometimes vary the strength of their claims by adjusting their understanding of the warrant. Some rationalists understand warranted beliefs to be beyond even the slightest doubtfulness; others are more than conservative and understand the warrant to be conventionalities beyond a reasonable doubt.

Rationalists also accept different understanding and claims involving the connection betwixt intuition and truth. Some rationalists merits that intuition is infallible and that anything nosotros intuit to be true is as such. More contemporary rationalists have that intuition is not e'er a source of certain knowledge – thus assuasive for the possibility of a deceiver who might cause the rationalist to intuit a false proposition in the same mode a 3rd party could cause the rationalist to have perceptions of nonexistent objects.

The innate noesis thesis [edit]

"We have knowledge of some truths in a item subject area, S, as part of our rational nature." [18]

The Innate Knowledge thesis is similar to the Intuition/Deduction thesis in the regard that both theses claim noesis is gained a priori. The two theses go their dissever means when describing how that noesis is gained. Equally the name, and the rationale, suggests, the Innate Knowledge thesis claims knowledge is simply part of our rational nature. Experiences can trigger a process that allows this cognition to come into our consciousness, but the experiences don't provide us with the knowledge itself. The knowledge has been with us since the beginning and the experience only brought into focus, in the same manner a photographer can bring the groundwork of a moving picture into focus past changing the discontinuity of the lens. The background was always at that place, only not in focus.

This thesis targets a trouble with the nature of inquiry originally postulated past Plato in Meno. Hither, Plato asks about enquiry; how exercise we proceeds knowledge of a theorem in geometry? We inquire into the matter. Yet, knowledge by research seems impossible.[nineteen] In other words, "If we already have the knowledge, at that place is no place for inquiry. If we lack the cognition, nosotros don't know what we are seeking and cannot recognize it when nosotros find information technology. Either way we cannot gain cognition of the theorem by inquiry. However, we exercise know some theorems."[18] The Innate Cognition thesis offers a solution to this paradox. By claiming that cognition is already with us, either consciously or unconsciously, a rationalist claims we don't really "learn" things in the traditional usage of the word, simply rather that we but bring to calorie-free what we already know.

The innate concept thesis [edit]

"Nosotros accept some of the concepts we employ in a item subject field area, S, every bit part of our rational nature." [20]

Similar to the Innate Cognition thesis, the Innate Concept thesis suggests that some concepts are simply part of our rational nature. These concepts are a priori in nature and sense feel is irrelevant to determining the nature of these concepts (though, sense experience can help bring the concepts to our conscious mind).

In his book, Meditations on First Philosophy,[21] René Descartes postulates three classifications for our ideas when he says, "Amidst my ideas, some announced to exist innate, some to be accidental, and others to accept been invented by me. My agreement of what a thing is, what truth is, and what idea is, seems to derive simply from my own nature. Simply my hearing a noise, as I do now, or seeing the dominicus, or feeling the fire, comes from things which are located outside me, or so I have hitherto judged. Lastly, sirens, hippogriffs and the like are my ain invention."[22]

Adventitious ideas are those concepts that we gain through sense experiences, ideas such as the awareness of heat, considering they originate from outside sources; transmitting their own likeness rather than something else and something you only cannot will away. Ideas invented past us, such as those found in mythology, legends, and fairy tales are created past us from other ideas we possess. Lastly, innate ideas, such as our ideas of perfection, are those ideas nosotros have as a result of mental processes that are beyond what experience can straight or indirectly provide.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz defends the idea of innate concepts by suggesting the mind plays a role in determining the nature of concepts, to explicate this, he likens the heed to a block of marble in the New Essays on Human Understanding,

This is why I have taken equally an illustration a cake of veined marble, rather than a wholly compatible block or blank tablets, that is to say what is called tabula rasa in the linguistic communication of the philosophers. For if the soul were similar those blank tablets, truths would be in the states in the same way every bit the figure of Hercules is in a block of marble, when the marble is completely indifferent whether it receives this or some other effigy. But if in that location were veins in the stone which marked out the figure of Hercules rather than other figures, this stone would be more adamant thereto, and Hercules would be every bit information technology were in some manner innate in it, although labour would be needed to uncover the veins, and to articulate them by polishing, and by cutting away what prevents them from actualization. It is in this way that ideas and truths are innate in united states, like natural inclinations and dispositions, natural habits or potentialities, and not like activities, although these potentialities are e'er accompanied past some activities which correspond to them, though they are often imperceptible."[23]

Some philosophers, such as John Locke (who is considered 1 of the near influential thinkers of the Enlightenment and an empiricist) argue that the Innate Cognition thesis and the Innate Concept thesis are the same.[24] Other philosophers, such as Peter Carruthers, contend that the two theses are distinct from i some other. As with the other theses covered nether the umbrella of rationalism, the more than types and greater number of concepts a philosopher claims to be innate, the more than controversial and radical their position; "the more than a concept seems removed from experience and the mental operations nosotros can perform on experience the more than plausibly it may be claimed to be innate. Since we do not feel perfect triangles but do feel pains, our concept of the former is a more promising candidate for being innate than our concept of the latter.[20]

History [edit]

Rationalist philosophy in Western antiquity [edit]

Although rationalism in its modern grade mail-dates antiquity, philosophers from this time laid down the foundations of rationalism.[ citation needed ] In detail, the understanding that we may be aware of knowledge available only through the employ of rational idea.[ citation needed ]

Pythagoras (570–495 BCE) [edit]

Pythagoras was i of the first Western philosophers to stress rationalist insight.[25] He is ofttimes revered as a great mathematician, mystic and scientist, simply he is best known for the Pythagorean theorem, which bears his name, and for discovering the mathematical relationship between the length of strings on lute and the pitches of the notes. Pythagoras "believed these harmonies reflected the ultimate nature of reality. He summed up the unsaid metaphysical rationalism in the words "All is number". Information technology is probable that he had caught the rationalist's vision, subsequently seen by Galileo (1564–1642), of a world governed throughout past mathematically formulable laws".[26] It has been said that he was the first man to telephone call himself a philosopher, or lover of wisdom.[27]

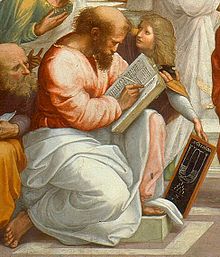

Plato (427–347 BCE) [edit]

Plato held rational insight to a very high standard, as is seen in his works such as Meno and The Democracy. He taught on the Theory of Forms (or the Theory of Ideas)[28] [29] [30] which asserts that the highest and most fundamental kind of reality is not the cloth earth of modify known to us through sensation, but rather the abstract, non-material (but substantial) world of forms (or ideas).[31] For Plato, these forms were accessible only to reason and not to sense.[26] In fact, it is said that Plato admired reason, especially in geometry, then highly that he had the phrase "Let no ane ignorant of geometry enter" inscribed over the door to his academy.[32]

Aristotle (384–322 BCE) [edit]

Aristotle's main contribution to rationalist thinking was the use of syllogistic logic and its use in statement. Aristotle defines syllogism as "a discourse in which certain (specific) things having been supposed, something unlike from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so."[33] Despite this very general definition, Aristotle limits himself to categorical syllogisms which consist of three categorical propositions in his work Prior Analytics.[34] These included categorical modal syllogisms.[35]

Middle Ages [edit]

Although the three great Greek philosophers disagreed with one another on specific points, they all agreed that rational thought could bring to light knowledge that was self-evident – data that humans otherwise could non know without the utilise of reason. After Aristotle's death, Western rationalistic thought was generally characterized by its application to theology, such every bit in the works of Augustine, the Islamic philosopher Avicenna (Ibn Sina), Averroes (Ibn Rushd), and Jewish philosopher and theologian Maimonides. Ane notable event in the Western timeline was the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas who attempted to merge Greek rationalism and Christian revelation in the thirteenth-century.[26] [36] More often than not, the Roman Cosmic Church viewed Rationalists equally a threat, labeling them as those who "while admitting revelation, reject from the word of God whatever, in their individual judgment, is inconsistent with human reason."[37]

Classical rationalism [edit]

Early modern rationalism has its roots in the 17th-century Dutch Democracy,[38] with some notable intellectual representatives similar Hugo Grotius,[39] René Descartes[a], and Baruch Spinoza[b].

René Descartes (1596–1650) [edit]

Descartes was the offset of the modern rationalists and has been dubbed the 'Father of Mod Philosophy.' Much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings,[40] [41] [42] which are studied closely to this mean solar day.

Descartes thought that only knowledge of eternal truths – including the truths of mathematics, and the epistemological and metaphysical foundations of the sciences – could be attained past reason lone; other knowledge, the cognition of physics, required experience of the world, aided by the scientific method. He too argued that although dreams appear equally real as sense experience, these dreams cannot provide persons with knowledge. Too, since conscious sense experience can be the cause of illusions, then sense experience itself can be suspect. As a event, Descartes deduced that a rational pursuit of truth should doubt every conventionalities nearly sensory reality. He elaborated these behavior in such works every bit Discourse on the Method, Meditations on First Philosophy, and Principles of Philosophy. Descartes developed a method to attain truths according to which nil that cannot be recognised by the intellect (or reason) tin can be classified equally knowledge. These truths are gained "without any sensory experience," according to Descartes. Truths that are attained by reason are broken down into elements that intuition tin can grasp, which, through a purely deductive process, volition upshot in clear truths about reality.

Descartes therefore argued, every bit a issue of his method, that reason alone adamant noesis, and that this could be done independently of the senses. For instance, his famous dictum, cogito ergo sum or "I remember, therefore I am", is a decision reached a priori i.east., prior to whatever kind of experience on the affair. The elementary significant is that doubting one's existence, in and of itself, proves that an "I" exists to do the thinking. In other words, doubting one's own doubting is cool.[25] This was, for Descartes, an irrefutable principle upon which to ground all forms of other cognition. Descartes posited a metaphysical dualism, distinguishing between the substances of the human body ("res extensa") and the listen or soul ("res cogitans"). This crucial distinction would be left unresolved and atomic number 82 to what is known as the heed-body problem, since the two substances in the Cartesian system are independent of each other and irreducible.

Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677) [edit]

In spite of his early death, Spinoza exerted a profound influence on philosophy in the Historic period of Reason.[43] [44] [45] He is ofttimes considered i of three most remarkable rationalists of modern Western thought, along with Descartes and Leibniz.

The philosophy of Baruch Spinoza is a systematic, logical, rational philosophy developed in seventeenth-century Europe.[46] [47] [48] Spinoza's philosophy is a arrangement of ideas constructed upon bones edifice blocks with an internal consistency with which he tried to answer life's major questions and in which he proposed that "God exists merely philosophically."[48] [49] He was heavily influenced by Descartes,[50] Euclid[49] and Thomas Hobbes,[50] as well as theologians in the Jewish philosophical tradition such equally Maimonides.[fifty] But his work was in many respects a divergence from the Judeo-Christian tradition. Many of Spinoza's ideas continue to vex thinkers today and many of his principles, particularly regarding the emotions, take implications for mod approaches to psychology. To this solar day, many of import thinkers have establish Spinoza's "geometrical method"[48] difficult to comprehend: Goethe admitted that he constitute this concept confusing.[ commendation needed ] His magnum opus, Ethics, contains unresolved obscurities and has a forbidding mathematical structure modeled on Euclid'south geometry.[49] Spinoza'due south philosophy attracted believers such as Albert Einstein[51] and much intellectual attention.[52] [53] [54] [55] [56]

Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) [edit]

Leibniz was the last major figure of seventeenth-century rationalism who contributed heavily to other fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, logic, mathematics, physics, jurisprudence, and the philosophy of religion; he is likewise considered to exist one of the final "universal geniuses".[57] He did not develop his system, all the same, independently of these advances. Leibniz rejected Cartesian dualism and denied the being of a cloth globe. In Leibniz's view there are infinitely many simple substances, which he called "monads" (which he derived directly from Proclus).

Leibniz developed his theory of monads in response to both Descartes and Spinoza, because the rejection of their visions forced him to arrive at his own solution. Monads are the fundamental unit of reality, according to Leibniz, constituting both inanimate and animate objects. These units of reality correspond the universe, though they are not subject to the laws of causality or infinite (which he called "well-founded phenomena"). Leibniz, therefore, introduced his principle of pre-established harmony to account for apparent causality in the earth.

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) [edit]

Kant is one of the primal figures of mod philosophy, and set the terms by which all subsequent thinkers have had to grapple. He argued that homo perception structures natural laws, and that reason is the source of morality. His idea continues to hold a major influence in contemporary thought, particularly in fields such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and aesthetics.[58]

Kant named his brand of epistemology "Transcendental Idealism", and he outset laid out these views in his famous work The Critique of Pure Reason. In it he argued that there were fundamental problems with both rationalist and empiricist dogma. To the rationalists he argued, broadly, that pure reason is flawed when it goes beyond its limits and claims to know those things that are necessarily beyond the realm of every possible feel: the existence of God, free will, and the immortality of the human soul. Kant referred to these objects as "The Affair in Itself" and goes on to debate that their status as objects across all possible experience by definition ways nosotros cannot know them. To the empiricist, he argued that while it is correct that experience is fundamentally necessary for human knowledge, reason is necessary for processing that experience into coherent thought. He therefore concludes that both reason and experience are necessary for homo knowledge. In the same way, Kant also argued that it was incorrect to regard thought as mere analysis. "In Kant's views, a priori concepts practise be, but if they are to pb to the amplification of knowledge, they must exist brought into relation with empirical data".[59]

Contemporary rationalism [edit]

Rationalism has get a rarer label of philosophers today; rather many different kinds of specialised rationalisms are identified. For example, Robert Brandom has appropriated the terms "rationalist expressivism" and "rationalist pragmatism" as labels for aspects of his programme in Articulating Reasons, and identified "linguistic rationalism", the claim that the contents of propositions "are essentially what can serve as both premises and conclusions of inferences", as a key thesis of Wilfred Sellars.[60]

See as well [edit]

- 17th-century philosophy

- Age of Reason

- Critical rationalism

- Foundationalism

- High german idealism

- Historical criticism

- Humanism

- Idealism

- Innatism

- Positivism

- Logical truth

- Natural philosophy

- Noetics

- Nominalism

- Noology

- Objectivity (philosophy)

- Objectivity (science)

- Pancritical rationalism

- Panrationalism

- Phenomenology (philosophy)

- Philosophical realism

- Ideal realism

- Rational realism

- Realistic rationalism

- Pluralistic rationalism

- Psychological nativism

- Rationalist International

- Rational mysticism

- Rationality and power

- Secular humanism

- Philosophy of Baruch Spinoza

- Tabula rasa

- Theistic rationalism

Notes [edit]

- ^

- Arthur Schopenhauer: "Descartes is rightly regarded every bit the father of modernistic philosophy primarily and generally because he helped the faculty of reason to stand on its ain feet past teaching men to use their brains in identify whereof the Bible, on the one hand, and Aristotle, on the other, had previously served." (Sketch of a History of the Doctrine of the Ideal and the Existent) [original in German language]

- Friedrich Hayek: "The nifty thinker from whom the basic ideas of what nosotros shall telephone call constructivist rationalism received their most complete expression was René Descartes. [...] Although Descartes' firsthand business concern was to establish criteria for the truth of propositions, these were inevitably besides applied by his followers to judge the appropriateness and justification of actions." (Police force, Legislation and Liberty, 1973)

- ^

- Georg Friedrich Hegel: "The philosophy of Descartes underwent a cracking variety of unspeculative developments, simply in Bridegroom Spinoza a direct successor to this philosopher may be institute, and i who carried on the Cartesian principle to its furthest logical conclusions." (Lectures on the History of Philosophy) [original in German]

- Hegel: "...Information technology is therefore worthy of note that idea must begin by placing itself at the standpoint of Spinozism; to be a follower of Spinoza is the essential commencement of all Philosophy." (Lectures on the History of Philosophy) [original in German]

- Hegel: "...The fact is that Spinoza is made a testing-point in modern philosophy, so that it may really be said: Y'all are either a Spinozist or not a philosopher at all." (Lectures on the History of Philosophy) [original in German]

- Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling: "...Information technology is unquestionably the peacefulness and calm of the Spinozist arrangement which particularly produces the idea of its depth, and which, with hidden but irresistible charm, has attracted and then many minds. The Spinozist arrangement will as well e'er remain in a certain sense a model. A arrangement of freedom—but with merely as great contours, with the aforementioned simplicity, every bit a perfect counter-image (Gegenbild) of the Spinozist system—this would really exist the highest system. This is why Spinozism, despite the many attacks on information technology, and the many supposed refutations, has never really become something truly past, never been really overcome up to at present, and no one can promise to progress to the true and the complete in philosophy who has not at to the lowest degree once in his life lost himself in the abyss of Spinozism." (On the History of Modern Philosophy, 1833) [original in German]

- Heinrich Heine: "...And besides, i could certainly maintain that Mr. Schelling borrowed more from Spinoza than Hegel borrowed from Schelling. If Spinoza is some day liberated from his rigid, antiquated Cartesian, mathematical form and made accessible to a large public, we shall possibly meet that he, more than any other, might mutter about the theft of ideas. All our present‑24-hour interval philosophers, possibly without knowing it, look through glasses that Baruch Spinoza basis." (On the History of Faith and Philosophy in Deutschland, 1836) [original in German]

- Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: "Spinozism dominated the eighteenth century both in its after French variety, which made matter into substance, and in deism, which conferred on thing a more than spiritual name.... Spinoza'due south French school and the supporters of deism were but two sects disputing over the true meaning of his system...." (The Holy Family, 1844) [original in German language]

- George Henry Lewes: "A brave and simple man, earnestly meditating on the deepest subjects that can occupy the human being race, he produced a system which will ever remain as ane of the well-nigh astounding efforts of abstract speculation—a system that has been decried, for nearly two centuries, as the nigh iniquitous and cursing of human invention; and which has now, inside the last threescore years, become the acknowledged parent of a whole nation'due south philosophy, ranking amid its admirers some of the most pious and illustrious intellects of the historic period." (A Biographical History of Philosophy, Vol. iii & 4, 1846)

- James Anthony Froude: "We may deny his conclusions; we may consider his organisation of thought preposterous and even pernicious, simply we cannot refuse him the respect which is the right of all sincere and honourable men. [...] Spinoza'south influence over European thought is too neat to be denied or gear up aside..." (1854)

- Arthur Schopenhauer: "In effect of the Kantian criticism of all speculative theology, the philosophisers of Germany almost all threw themselves back upon Spinoza, so that the whole series of futile attempts known past the proper name of the mail service-Kantian philosophy are just Spinozism tastelessly dressed up, veiled in all kinds of unintelligible language, and otherwise distorted..." (The Globe as Will and Idea, 1859) [original in German]

- Due south. Yard. Melamed: "The rediscovery of Spinoza by the Germans contributed to the shaping of the cultural destinies of the German people for almost two hundred years. Just as at the time of the Reformation no other spiritual strength was equally potent in German life as the Bible, and then during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries no other intellectual forcefulness and so dominated German life as Spinozism. Spinoza became the magnet to High german steel. Except for Immanuel Kant and Herbart, Spinoza attracted every great intellectual figure in Deutschland during the last two centuries, from the greatest, Goethe, to the purest, Lessing." (Spinoza and Buddha: Visions of a Expressionless God, University of Chicago Press, 1933)

- Louis Althusser: "Spinoza'southward philosophy introduced an unprecedented theoretical revolution in the history of philosophy, probably the greatest philosophical revolution of all time, insofar as we tin can regard Spinoza as Marx's only direct ancestor, from the philosophical standpoint. However, this radical revolution was the object of a massive historical repression, and Spinozist philosophy suffered much the same fate equally Marxist philosophy used to and still does suffer in some countries: it served as damning evidence for a charge of 'atheism'." (Reading Uppercase, 1968) [original in French]

- Frederick C. Beiser: "The rise of Spinozism in the tardily eighteenth century is a miracle of no less significance than the emergence of Kantianism itself. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Spinoza'southward philosophy had get the main competitor to Kant'due south, and just Spinoza had as many admirers or adherents equally Kant." (The Fate of Reason: German language Philosophy from Kant to Fichte, 1987)

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b c d "Rationalism". Britannica.com.

- ^ a b Lacey, A.R. (1996), A Dictionary of Philosophy, 1st edition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976. 2nd edition, 1986. 3rd edition, Routledge, London, UK, 1996. p. 286

- ^ a b Bourke, Vernon J., "Rationalism," p. 263 in Runes (1962).

- ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Rationalism vs. Empiricism First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Audi, Robert, The Cambridge Lexicon of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1995. 2nd edition, 1999, p. 771.

- ^ Gottlieb, Anthony: The Dream of Enlightenment: The Rise of Mod Philosophy. (London: Liveright Publishing [Due west. W. Norton & Company], 2016)

- ^ Lavaert, Sonja; Schröder, Winfried (eds.): The Dutch Legacy: Radical Thinkers of the 17th Century and the Enlightenment. (Leiden: Brill, 2016)

- ^ Russell, Bertrand: A History of Western Philosophy. (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1946). Bertrand Russell: "He [Descartes] lived in Kingdom of the netherlands for xx years (1629–49), except for a few cursory visits to France and one to England, all on business concern. It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of Holland in the seventeenth century, every bit the one land where at that place was liberty of speculation."

- ^ Hampshire, Stuart: The Age of Reason: The 17th Century Philosophers. Selected, with Introduction and Commentary. (New York: Mentor Books [New American Library], 1956)

- ^ James, William (Nov 1906). The Nowadays Dilemma in Philosophy (Oral communication). Lowell Institute.

- ^ Oakeshott, Michael,"Rationalism in Politics," The Cambridge Journal 1947, vol. 1 Retrieved 2013-01-xiii.

- ^ Boyd, Richard, "The Value of Civility?," Urban Studies Journal, May 2006, vol. 43 (no. 5–6), pp. 863–78 Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ^ FactCheck.org Mission Statement, January 2020 Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- ^ Cottingham, John. 1984. Rationalism. Paladi/Granada

- ^ Sommers (2003), p. xv.

- ^ a b c Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Intuition/Deduction Thesis First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ 1704, Gottfried Leibniz Preface, pp. 150–151

- ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Innate Knowledge Thesis First published August 19, 2004; substantive revision March 31, 2013 cited on May 20, 2013.

- ^ Meno, 80d–due east

- ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Innate Concept Thesis First published August nineteen, 2004; noun revision March 31, 2013 cited on May xx, 2013.

- ^ Cottingham, J., ed. (April 1996) [1986]. Meditations on Beginning Philosophy With Selections from the Objections and Replies (revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-55818-one. –The original Meditations, translated, in its entirety.

- ^ René Descartes AT Vii 37–eight; CSM Two 26

- ^ Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, 1704, New Essays on human Understanding, Preface, p. 153

- ^ Locke, Concerning Human Agreement, Book I, Ch. 3, par. 20

- ^ a b "rationalism | Definition, Types, History, Examples, & Descartes". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c "Rationalism".

- ^ Cicero, Tusculan Disputations, v.3.viii–9 = Heraclides Ponticus fr. 88 Wehrli, Diogenes Laërtius i.12, viii.8, Iamblichus VP 58. Burkert attempted to discredit this ancient tradition, but it has been defended by C.J. De Vogel, Pythagoras and Early Pythagoreanism (1966), pp. 97–102, and C. Riedweg, Pythagoras: His Life, Pedagogy, And Influence (2005), p. 92.

- ^ Modernistic English language textbooks and translations prefer "theory of Form" to "theory of Ideas," simply the latter has a long and respected tradition starting with Cicero and continuing in High german philosophy until present, and some English philosophers prefer this in English likewise. See W D Ross, Plato'south Theory of Ideas (1951) and this Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Auto reference site.

- ^ The name of this attribute of Plato's idea is non modern and has not been extracted from sure dialogues by modernistic scholars. The term was used at least as early equally Diogenes Laërtius, who called information technology (Plato's) "Theory of Forms:" Πλάτων ἐν τῇ περὶ τῶν ἰδεῶν ὑπολήψει ...., "Plato". Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Vol. Book III. pp. Paragraph fifteen.

- ^ Plato uses many dissimilar words for what is traditionally called form in English translations and idea in German and Latin translations (Cicero). These include idéa, morphē, eîdos, and parádeigma, but as well génos, phýsis, and ousía. He likewise uses expressions such as to x car, "the x itself" or kath' auto "in itself." Run across Christian Schäfer: Idee/Form/Gestalt/Wesen, in Platon-Lexikon, Darmstadt 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Forms (usually given a capital F) were backdrop or essences of things, treated equally non-material abstract, but substantial, entities. They were eternal, invariable, supremely existent, and independent of ordinary objects that had their being and backdrop by 'participating' in them. Plato's theory of forms (or ideas) Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ SUZANNE, Bernard F. "Plato FAQ: "Permit no one ignorant of geometry enter"". plato-dialogues.org.

- ^ Aristotle, Prior Analytics, 24b18–20

- ^ [1] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Ancient Logic Aristotle Non-Modal Syllogistic

- ^ [2] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Ancient Logic Aristotle Modal Logic

- ^ Gill, John (2009). Andalucía : a cultural history. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN978-0-xix-537610-four.

- ^ Bellarmine, Robert (1902). . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- ^ Lavaert, Sonja; Schröder, Winfried: The Dutch Legacy: Radical Thinkers of the 17th Century and the Enlightenment. (BRILL, 2016, ISBN 978-9004332072)

- ^ Berolzheimer, Fritz: The World'south Legal Philosophies. Translated by Rachel Szold. (New York: The MacMillan Co., 1929. lv, 490 pp. Reprinted 2002 past The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd). As Fritz Berolzheimer noted, "Equally the Cartesian "cogito ergo sum" became the point of departure of rationalistic philosophy, so the establishment of authorities and law upon reason made Hugo Grotius the founder of an contained and purely rationalistic system of natural police."

- ^ Bertrand Russell (2004) History of western philosophy pp. 511, 516–17

- ^ Heidegger [1938] (2002) p. 76 "Descartes... that which he himself founded... mod (and that means, at the same time, Western) metaphysics."

- ^ Watson, Richard A. (31 March 2012). "René Descartes". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Durant, Will; Ariel, Durant: The Story of Civilization: The Age of Reason Begins (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961).

- ^ Nadler, Steven, "Baruch Spinoza", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ Popkin, Richard H., "Bridegroom de Spinoza", Encyclopædia Britannica, (2017 Edition)

- ^ Lisa Montanarelli (book reviewer) (January 8, 2006). "Spinoza stymies 'God's attorney' – Stewart argues the secular world was at stake in Leibniz face off". San Francisco Chronicle . Retrieved 2009-09-08 .

- ^ Kelley L. Ross (1999). "Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677)". History of Philosophy As I Come across Information technology. Retrieved 2009-12-07 .

While for Spinoza all is God and all is Nature, the active/passive dualism enables usa to restore, if nosotros wish, something more than like the traditional terms. Natura Naturans is the most God-like side of God, eternal, unchanging, and invisible, while Natura Naturata is the nigh Nature-like side of God, transient, changing, and visible.

- ^ a b c Anthony Gottlieb (July eighteen, 1999). "God Exists, Philosophically". The New York Times: Books. Retrieved 2009-12-07 .

Spinoza, a Dutch Jewish thinker of the 17th century, not simply preached a philosophy of tolerance and benevolence but actually succeeded in living it. He was reviled in his ain day and long afterward for his supposed disbelief, yet fifty-fifty his enemies were forced to admit that he lived a saintly life.

- ^ a b c ANTHONY GOTTLIEB (2009-09-07). "God Exists, Philosophically (review of "Spinoza: A Life" by Steven Nadler)". The New York Times – Books. Retrieved 2009-09-07 .

- ^ a b c Michael LeBuffe (book reviewer) (2006-11-05). "Spinoza'southward Ideals: An Introduction, by Steven Nadler". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 2009-12-07 .

Spinoza's Ethics is a contempo addition to Cambridge's Introductions to Key Philosophical Texts, a series developed for the purpose of helping readers with no specific background knowledge to begin the written report of of import works of Western philosophy...

- ^ "EINSTEIN BELIEVES IN "SPINOZA'South GOD"; Scientist Defines His Faith in Reply, to Buzzer From Rabbi Here. SEES A DIVINE Guild But Says Its Ruler Is Not Concerned "Wit Fates and Actions of Human Beings."". The New York Times. April 25, 1929. Retrieved 2009-09-08 .

- ^ Hutchison, Percy (November 20, 1932). "Spinoza, "God-Intoxicated Man"; Three Books Which Marking the Iii Hundredth Ceremony of the Philosopher'south Nativity Blessed SPINOZA. A Biography. By Lewis Browne. 319 pp. New York: Macmillan. SPINOZA. Liberator of God and Human. Past Benjamin De Casseres, 145 pp. New York: Eastward.Wickham Sweetland. SPINOZA THE BIOSOPHER. Past Frederick Kettner. Introduction by Nicholas Roerich, New Era Library. 255 pp. New York: Roerich Museum Press. Spinoza". The New York Times . Retrieved 2009-09-08 .

- ^ "Spinoza'southward Outset Biography Is Recovered; THE OLDEST BIOGRAPHY OF SPINOZA. Edited with Translations, Introduction, Annotations, &c., by A. Wolf. 196 pp. New York: Lincoln Macveagh. The Dial Press". The New York Times. Dec 11, 1927. Retrieved 2009-09-08 .

- ^ IRWIN EDMAN (July 22, 1934). "The Unique and Powerful Vision of Baruch Spinoza; Professor Wolfson's Long-Awaited Book Is a Piece of work of Illuminating Scholarship. (Book review) THE PHILOSOPHY OF SPINOZA. By Henry Austryn Wolfson". The New York Times . Retrieved 2009-09-08 .

- ^ Cummings, M East (September 8, 1929). "ROTH EVALUATES SPINOZA". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 2009-09-08 .

- ^

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

- ^ "Immanuel Kant (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 2011-10-22 .

- ^ "Rationalism". abyss.uoregon.edu.

- ^ Articulating reasons, 2000. Harvard Academy Press.

References [edit]

Master sources [edit]

- Descartes, René (1637), Discourse on the Method.

- Spinoza, Baruch (1677), Ethics.

- Leibniz, Gottfried (1714), Monadology.

- Kant, Immanuel (1781/1787), Critique of Pure Reason.

Secondary sources [edit]

- Audi, Robert (ed., 1999), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Uk, 1995. 2nd edition, 1999.

- Baird, Forrest Eastward.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN978-0-13-158591-1.

- Blackburn, Simon (1996), The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, Oxford University Printing, Oxford, Uk, 1994. Paperback edition with new Chronology, 1996.

- Bourke, Vernon J. (1962), "Rationalism," p. 263 in Runes (1962).

- Douglas, Alexander 10.: Spinoza and Dutch Cartesianism: Philosophy and Theology. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015)

- Fischer, Louis (1997). The Life of Mahatma Gandhi. Harper Collins. pp. 306–07. ISBN0-00-638887-half-dozen.

- Förster, Eckart; Melamed, Yitzhak Y. (eds.): Spinoza and German Idealism. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012)

- Fraenkel, Carlos; Perinetti, Dario; Smith, Justin E. H. (eds.): The Rationalists: Between Tradition and Innovation. (Dordrecht: Springer, 2011)

- Hampshire, Stuart: Spinoza and Spinozism. (Oxford: Clarendon Printing; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005)

- Huenemann, Charles; Gennaro, Rocco J. (eds.): New Essays on the Rationalists. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

- Lacey, A.R. (1996), A Lexicon of Philosophy, 1st edition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1976. 2nd edition, 1986. 3rd edition, Routledge, London, UK, 1996.

- Loeb, Louis Due east.: From Descartes to Hume: Continental Metaphysics and the Evolution of Modernistic Philosophy. (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1981)

- Nyden-Bullock, Tammy: Spinoza's Radical Cartesian Mind. (Continuum, 2007)

- Pereboom, Derk (ed.): The Rationalists: Critical Essays on Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz. (Lanham, Dr.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

- Phemister, Pauline: The Rationalists: Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz. (Malden, MA: Polity Printing, 2006)

- Runes, Dagobert D. (ed., 1962), Dictionary of Philosophy, Littlefield, Adams, and Company, Totowa, NJ.

- Strazzoni, Andrea: Dutch Cartesianism and the Birth of Philosophy of Science: A Reappraisal of the Function of Philosophy from Regius to 's Gravesande, 1640–1750. (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018)

- Verbeek, Theo: Descartes and the Dutch: Early Reactions to Cartesian Philosophy, 1637–1650. (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992)

External links [edit]

- Zalta, Edward Northward. (ed.). "Rationalism vs. Empiricism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Rationalism at PhilPapers

- Rationalism at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Homan, Matthew. "Continental Rationalism". Cyberspace Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Lennon, Thomas M.; Dea, Shannon. "Continental Rationalism". In Zalta, Edward Northward. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- John F. Hurst (1867), History of Rationalism Embracing a Survey of the Present State of Protestant Theology

edwardsworgalenly.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rationalism

0 Response to "German Art History and Scientific Thought Beyond Formalism"

Postar um comentário