Where to Find Muric Acid to Clean Bricks

Photo courtesy Prosoco and Brick Industry Association

In many instances, brick's tendency to effloresce can be determined prior to laying. To conduct this test, a brick is placed on end in a pan of distilled water for seven days. Water is allowed to migrate upward through the brick and evaporate on the surface. If the brick is prone to efflorescence, soluble salts will be deposited on its surface during evaporation. Distilled water ensures additional impurities are not introduced into the brick from the water.

Sources of salt and moisture

Examples of moisture sources include:

- construction activities (e.g. concreting, mixing mortar, plastering, fireproofing, and drywall installation);

- exterior sources (e.g. weather [rain, fog, condensation, humidity, and snow], landscaping irrigation, and groundwater);

- interior sources (e.g. cooking, showering, breathing, plumbing failures, drainage failures, missing or damaged vapor retarders, groundwater through the foundation, and failed or missing internal flashing); and

- installation problems (e.g. improper use of through-wall flashing, lack of sufficient weep holes, masonry without vented cavity, use of incorrect brick below-grade or at planter-type areas without a proper moisture barrier, failure of joint materials, or no integral water repellent in mortar or CMU).

The salts usually associated with efflorescence are alkali sulfates such as sodium and potassium. Sources of these salts include portland cement, lime, sand (source may be from sea shore), clay used in the brick (may come from saline earth), and any of the admixture containing chlorine. Even water that was in contact with sulfate-containing soil can produce efflorescence.

Efflorescence is also affected by the permeability of construction materials. The more porous the materials, the more they can transport moisture. Thus, smooth brick are less porous than textured brick, tooled mortar joints are less porous than untooled mortar, and standard-weight CMU is less porous than lightweight. Similarly, regular CMU is less porous than split-face, concrete with a steel trowel finish is less porous than a float finish, and architectural precast concrete panels with 41,368.5 to 48,263 kPa (6000 to 7000 psi) compressive strength are less permeable than 20,684-kPa (3000-psi) concrete.

Proper tooling masonry joints causes the cement paste to encapsulate the fine aggregate in a smooth dense matrix, forming a water-resistant joint. When masonry is pressure-washed, the chemical cleaner can damage or remove the cement matrix along with the joint's water resistance.

Rain can easily enter a masonry wall that is under construction through its exposed top. Water can fill the cells in the brick and CMU units and then irrigate the walls long after completion. If the walls are reinforced, the pools of water in the cells can affect grout pours.

Removing efflorescence

Cleaning efflorescence only removes the visible symptoms—it does not necessarily cure the disease. So long as the causes are still present, efflorescence will keep reappearing.

Soft dry brush

If the salts are water-soluble, a dry brush with bristles stiff enough to remove the efflorescence, but not stiff enough to damage the surface of the substrate, may be used. Brushing actually removes the salts and prevents them from being driven back into the structure, as is often the case with fresh water and chemical treatment. This should be the preferred method because there is no detrimental effect on the surfaces.

Fresh water

Washing with fresh water is the next-best method. However, since moisture is one of the factors leading to efflorescence, washing also introduces more moisture into the wall. The paths the salts take to the surface are not one-way; some of the partially dissolved salts may be carried back into the structure through the same path that took them to the surface.

Manual washing can often draw additional salts to the surface. Repeat washing may be necessary, but when all the salts have come to the surface naturally and have been washed off, there will usually be no more trouble from this cause. It is imperative all efflorescence mechanisms are reduced or eliminated before sealing. If efflorescence does not return, chances are the moisture and/or salts were construction-induced.

Chemical

Probably the most common removal method, chemical cleaners can contain acids or detergents that dissolve the salts so they can be washed away with fresh water. The acids in the cleaner can react with pigments potentially in brick, concrete, or mortar, producing color variations.

Often, chemical cleaning cannot remove crystalline efflorescence because of the crystals' attachment to the surface. This is why surfaces cleaned with chemical cleaning methods can look great for a few hours, but deposits are still visible once the surfaces dry. Contrary to what some may think, these are not new deposits emerging—they were existing ones temporarily disguised by the darkening effect of the initial treatment. The reappearing efflorescence is usually crystalline and is bonded to the surface. These deposits will 'fizz' on contact with strong acids (e.g. muriatic), which should not be used to clean masonry.

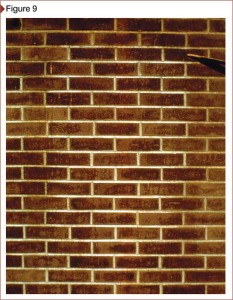

Chemical cleaning can produce acid burn if not properly performed by trained professionals (Figure 9). Although not considered efflorescence, muriatic acid frequently causes this burn; the brick's porosity causes the acid to be absorbed before it can be properly rinsed. Improper chemical cleaning can also activate any metallic salts that may be dormant in the structure, resulting in stubborn brown and green stains instead of a stain-free structure. Therefore, these stains are not normally visible until after chemical cleaning.

Pages: 1 2 3 4

Where to Find Muric Acid to Clean Bricks

Source: https://www.constructionspecifier.com/why-red-brick-turns-white-understanding-efflorescence/3/

0 Response to "Where to Find Muric Acid to Clean Bricks"

Postar um comentário